Thin-layer chromatography, known as TLC, is one of the fundamental and most widely used analytical techniques in chemistry and biology. Due to its simplicity, speed and low cost, it is an invaluable tool in laboratories around the world. It allows rapid separation, identification and preliminary quantitative analysis of components of complex mixtures.

What is chromatography

Chromatography is a technique for separating mixtures in which substances transported through a mobile phase pass through a stationary phase. A separation of the substances is a result of the differences in the interactions between the substances and the stationary phase. Read more about the basics of chromatography here.

What is thin-layer chromatography?

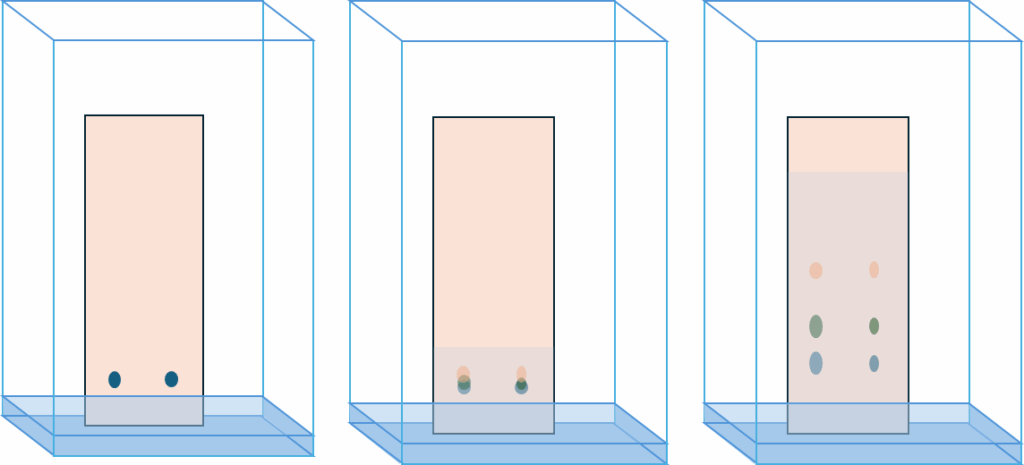

Thin-layer chromatography is a planar chromatography technique that is used to separate the components of a mixture. The process takes place on a plate covered with a thin layer of adsorption material, called the stationary phase. The mixture, applied as a small dot or line on the plate, is developed by a solution of solvent. Solvents are called the mobile phase or eluent. The eluent moves up the plate thanks to capillary forces. As the mobile phase moves up the plate, the individual components of the mixture travel at different speeds. This leads to their separation. Such an experimental set-up is called ascending chromatography (from ascending mobile phase).

Two other separation methods are also used in liquid-layer chromatography:

- Descending chromatography: the mobile phase is contained in a vessel located at the top of the chamber. It is brought to the bottom by a strip of blotting paper

- Horizontal chromatography – requires a special chamber. The mobile phase is contained in a vessel in one part of the chamber and passes into the other vessel with the aid of a blotting paper. Horizontal chromatography is suitable for separating slowly migrating molecules of similar structure. It provides high resolution.

Mechanism of separation in thin-layer chromatography

The basis of separation in thin-layer chromatography is the differential interaction between analyte, mobile phase and stationary phase. The two main mechanisms responsible for this are adsorption and partitioning. For this reason, thin-layer chromatography is divided into:

- Adsorption chromatography (most common in TLC): The stationary phase (e.g. silica gel) is more polar than the mobile phase (usually a mixture of organic solvents). The polar components of the mixture interact (adsorb) more strongly with the polar stationary phase and travel more slowly. The less polar components are less strongly adsorbed and travel faster with the mobile phase.

- Partition chromatography: In this case, a liquid (e.g. water) is deposited on a carrier (stationary phase). The separation is based on differences in the solubility of the analytes between the stationary liquid layer and the mobile phase.

In practice, the final separation is the result of complex interactions, including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds and dipole-dipole interactions.

Types of stationary phases in thin-layer chromatography

Choosing the right stationary phase is crucial for successful separation. The most popular of these are:

- Silica gel: the most commonly used stationary phase. It is acidic in nature and highly polar due to the presence of silanol groups (-Si-OH). Ideal for the separation of compounds of varying polarity, such as amino acids, alkaloids or sugars.

- Aluminium oxide: Has a slightly alkaline to neutral character. It is used for the separation of basic compounds, such as amines, and for the separation of inert compounds, such as hydrocarbons or steroids.

- Cellulose: Polymer of glucose exhibiting a polar nature. Allows separation by a partitioning mechanism, where the stationary phase is water bound to cellulose fibres. Excellent for the analysis of hydrophilic compounds, e.g. amino acids and nucleotides.

- Surface-modified phases (reversed phases, RP): These are phases in which the polar groups of the silica gel have been chemically modified by the attachment of non-polar hydrocarbon chains (e.g. C8, C18). In this system, the stationary phase is non-polar and the mobile phase is polar (e.g. mixtures of water with methanol or acetonitrile). This mechanism is called reversed-phase chromatography (RP-TLC).

Below are examples of the use of different stationary phases:

| Adsorbent | Separation mechanism | Example of analytes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica gel | adsorption, partitioning | almost all |

| Aluminium oxide | adsorption, partitioning | alkali and steroids |

| Siliceous soil | partiotioning | sugars, higher fatty acids |

| Magnesium phosphate, magnesium silicate, calcium hydroxide, calcium phosphate | adsorption | karetonoids and tocopherols |

| Coal | adsorption | non-polar compounds |

| Ion exchangers | exchange | nucleic acids |

How to select the mobile phase?

The selection of the mobile phase (eluent) is an optimisation process that aims to achieve the best possible separation (differences in migration velocity) of the analytes. The key principles are:

- The “like dissolves like” rule is reversed here: in order for a substance to move across a plate, the mobile phase must have the ability to “wash” it from the stationary phase.

- Polarity of the eluent: The elution power of a solvent (its ability to move analytes up the plate) depends on its polarity.

- In the case of normal phases (e.g. silica gel), the more polar the eluent, the more strongly it interacts with the stationary phase, competing with the analytes for active sites and thus accelerating their migration.

- In the case of reversed phases, the less polar the eluent, the greater its elution force.

- Eluotropic series: In thin-layer chromatography, it is not possible to perform gradient separation (such as in HPLC). Instead, a so-called eluotropic series can be used. In short, one uses successive solvents of increasing elution strength. Example series (from weakest to strongest eluent): hexane < toluene < chloroform < ethyl acetate < acetone < ethanol < methanol.

- Solvent mixtures: A single solvent is rarely used. Most often mixtures are used, e.g. hexane with ethyl acetate. By varying the proportions of the components, the polarity of the eluent can be precisely ‘tuned’ and optimal Rf values can be obtained (see below).

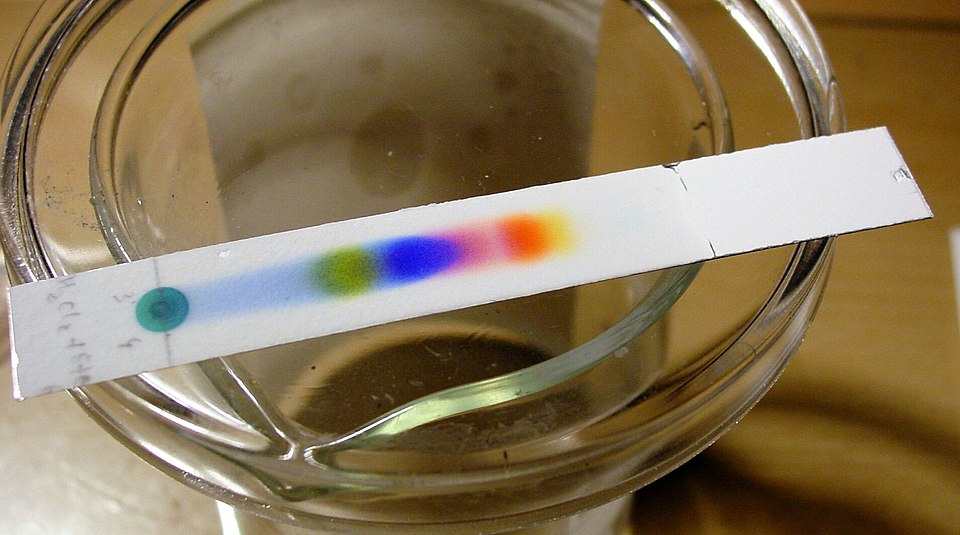

TLC chromatogram staining and detection

If the separated substances are colourful, they can be observed with the bare eye. However, they are usually colourless and require special detection methods:

- UV light: Many TLC plates contain a fluorescent indicator that emits green light when exposed to UV light at 254 nm. Compounds that absorb UV light quench this fluorescence and appear as dark spots. Other compounds may themselves fluoresce.

- Iodine vapour: The plate is placed in a chamber saturated with iodine vapour. Iodine is adsorbed onto the surface of the analytes (especially organic compounds), leading to the appearance of yellow or brown spots. This method is versatile and usually reversible.

- Staining reagents (sprays): These are chemical solutions with which the plate is sprayed. They react with specific functional groups of analytes to give coloured products. Here are examples of some staining reagents

- Ninhydrin: for detection of amino acids (gives purple spots).

- Potassium permanganate (KMnO4): for the detection of readily oxidisable compounds, e.g. unsaturated compounds (yellow spots appear on a violet background).

- Vanillin solution in sulphuric acid: universal stain for many organic compounds, gives a wide range of colours when the plate is heated.

Calculations

Staining the chromatogram, making the spots visible, is only the beginning of the analysis of the results. Each spot is one of the separated substances. They still need to be identified. A basic parameter that helps to identify substances is the retardation factor (Rf)

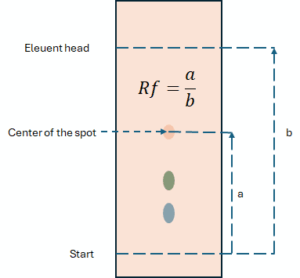

How do you determine the Rf (retardation factor)?

The retardation factor (Rf) is a fundamental parameter in planar chromatography, describing the position of a spot on the chromatogram. It is the ratio of the path travelled by the substance to the path travelled by the eluent front.

Rf= a/b

Where:

- a – distance from the start line to the centre of the analyte spot.

- b – the distance from the starting line to the line of the mobile phase front.

The Rf value is always less than 1. Under ideal conditions, it is constant for a given compound, stationary phase and mobile phase, allowing initial identification of the substance by comparison with a standard.

Densitometry

Densitometry is an instrumental technique that transforms TLC from a qualitative to a quantitative method. It involves measuring the amount of light reflected or transmitted through a spot on a chromatogram using a special scanner (densitometer). In the case of coloured substances or the use of developing reagents, an ordinary scanner or even a camera can be used. Image processing and calculations are performed by a special computer software. The intensity of the signal (peak area) is proportional to the concentration of the substance in the spot. This allows the quantification of individual components in the sample under investigation on a similar basis to HPLC.

Application – examples

The versatility of TLC makes it applicable in many fields:

- Pharmacy and medicine:

- Controlling the purity of active substances and medicinal products.

- Monitoring the reaction of organic synthesis.

- Clinical diagnosis, e.g. testing for the presence of drugs or drugs in body fluids (blood, urine).

- Food industry:

- Detection of pesticides and preservatives.

- Analysis of food colours (natural and synthetic).

- Identification of mycotoxins (e.g. aflatoxins) in food.

- Environmental protection:

- Analysis of contaminants in water and soil (e.g. polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – PAHs).

- Cosmetology

- Identification and purity control of cosmetic ingredients, e.g. preservatives or UV filters.

- Forensics:

- Trace analysis (e.g. ink from documents, dyes from fibres).

- Drug content testing (e.g. THC in drug samples, plants, etc.).

Summary

Thin-layer chromatography is a powerful, rapid and inexpensive analytical technique that, despite the development of more advanced methods, is still indispensable in many laboratories. Its simplicity of execution, ability to analyse multiple samples simultaneously and ease of visualisation of results make it an excellent tool for both research and educational purposes. From chemical reaction monitoring to clinical analysis, TLC proves that sometimes the simplest solutions are the most elegant.

Library

- Kłyszejko – Stefanowicz L. (2003). Ćwiczenia z biochemii. PWN

- Wall, P. E. (2005). Thin-layer Chromatography: A Modern Practical Approach. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Spangenberg, B., Poole, C. F., & Weins, C. (Eds.). (2011). Quantitative Thin-Layer Chromatography: A Practical Survey. Springer.

- https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Analytical_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Analytical_Chemistry)/Instrumental_Analysis/Chromatography/Thin_Layer_Chromatography

- Cygański, A. (2018). Metody Spektroskopowe w Chemii Analitycznej. Wydawnictwo WNT. (Książka ta często zawiera rozdziały o metodach separacyjnych jako technikach pomocniczych).

- Witkiewicz, Z. (2000). Podstawy chromatografii. Wydawnictwo WNT.