HPLC, or high-performance liquid chromatography, is an analytical technique without which the modern pharmaceutical and chemical industries would not exist. Today, thousands of different HPLC devices are used in research laboratories and quality control departments of industrial and research facilities around the world. This article is the first in a series devoted to HPLC and is intended to introduce the subject.

What is HPLC?

Chromatography itself is a method of separating mixtures into individual components based on their different affinities to two phases: the mobile phase (eluent) and the stationary phase (column packing). You can find more on this topic in this article.

The difference between classical chromatography and HPLC

In classical liquid chromatography (column chromatography), the mobile phase moves through the column under the influence of small forces. This can be gravity or a small flow obtained by a pump. It is a slow process and is characterised by low resolution.

In HPLC, the situation changes dramatically. The key to success is the use of very fine packing particles (usually between 1.8 and 5 μm). The smaller the particles, the greater the exchange surface area and the better the separation, but at the same time, the greater the resistance to the flowing liquid. To overcome this, high pressure is required (reaching 400 bar in classic HPLC and over 1000 bar in UHPLC systems). The use of fine particles results in greater separation capacity and shorter analysis times. In general, HPLC columns are smaller than columns for low-pressure chromatography. This makes it possible to reduce the amount of sample required for analysis.

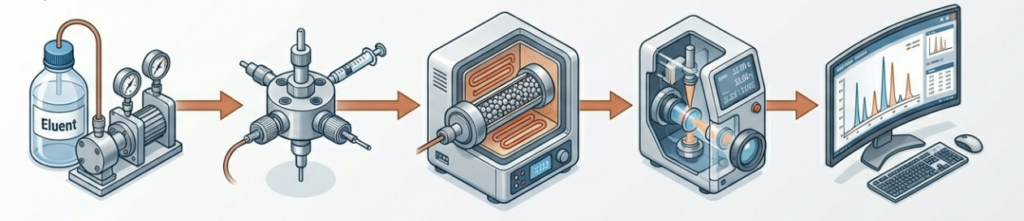

How is HPLC constructed?

An HPLC apparatus, commonly referred to as a chromatograph, is an advanced modular system. Each component plays a critical role in the analytical process.

Pumps (Solvent delivery system)

The pump is the basis of the system. It must deliver the mobile phase at a constant flow rate (e.g. 1 ml/min) under high pressure. It is important that the flow of the mobile phase is stable, without pulsation.

The pump can operate in two different modes: isocratic and gradient. There are also two types of elution:

- Isocratic: The composition of the mobile phase remains constant throughout the analysis.

- Gradient: The composition of the phase changes over time (e.g. the concentration of the organic solvent increases), which allows for faster separation of complex mixtures.

Injector

The point at which the sample is introduced into the system. In simple HPLC systems, the syringe port and injection loop act as the injector. The purpose of the loop is to precisely control the volume of the sample introduced into the system.

Nowadays, autosamplers are used, which automatically collect a precise volume and introduce it into the high-pressure eluent stream using a special valve (Rheodyne type). The advantage of autosamplers is convenience (the operator does not have to manually introduce the sample before each analysis) and efficiency (they allow you to automate the work and queue up even thousands of samples)

Chromatography column

The most important element in which proper separation takes place. Often placed in a so-called oven (i.e. a thermostabilised compartment for columns) to maintain a constant temperature, which affects the repeatability of retention times. The oven also allows the column to be heated or cooled. Temperature can significantly affect the separation capacity of the column. Cooling enables the analysis of thermolabile compounds.

Detector

A device for monitoring the composition of leaks from columns. The most commonly used detectors include:

- UV-Vis / DAD (Diode Array Detector): It measures the absorption of light by chemical compounds.

- Fluorescent: Highly sensitive, for compounds capable of fluorescence.

- Mass spectrometer (MS): Allows the structure of molecules to be identified.

Recording system (Data system)

Software that collects signals from the detector and converts them into a chromatogram – a graph showing the relationship between signal and time.

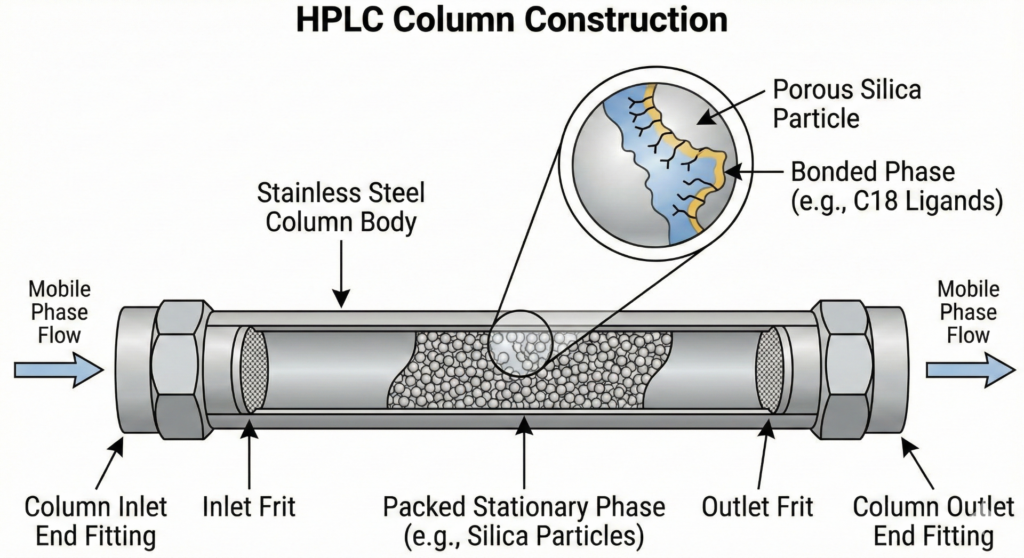

Construction and role of the HPLC column

An HPLC column is a precision engineering device that must withstand enormous mechanical and chemical stresses.

Steel casing

The outer part of the column is made of high-grade stainless steel (usually type 316), polished on the inside to minimise friction and flow turbulence.

Filling (Stationary phase)

Most often, it is silica gel. The gel has the form of grains with a porous structure. The surface of silica is chemically modified by attaching various functional groups, which determines the nature of interactions with analytes. Columns with uniform filling are also available.

Porous filters

There are steel frits at both ends of the column. Their purpose is to:

- Maintaining the filling inside the column.

- Preliminary filtering of the sample and mobile phase to prevent clogging of fine grains.

Types of columns and distribution mechanisms

The choice of column depends on the physicochemical properties of the substances being analysed.

Reverse Phase (RP)

This is the most common technique (approx. 80% of all analyses).

- Stationary phase: Non-polar (e.g. C18, C8 carbon chains).

- Mobile phase: Polar (water, methanol, acetonitrile).

- Principle: More polar compounds elute (flow out) first, while more “fatty” (hydrophobic) compounds remain longer.

Normal Phase (NP)

Historically the first, today used less frequently (e.g. for the separation of isomers).

- Stationary phase: Polar (pure silica).

- Mobile phase: Non-polar (hexane, heptane).

- Principle: Non-polar compounds flow out quickly, polar compounds are strongly retained.

Ion exchange chromatography (IEX)

It is used to separate ions and charged molecules (e.g. proteins, amino acids). It utilises the electrostatic attraction between the analyte and charged groups on the surface of the packing.

Exclusion Chromatography (SEC/GPC)

Separation occurs based on particle size. Larger molecules that do not fit into the filling pores bypass them and flow out the fastest. Small molecules “enter” the maze of pores, which lengthens their path.

Types of HPLC and its applications

Reading this article, HPLC appears to be an excellent analytical tool. In fact, it is most widely used in analytical laboratories. Here are the areas in which it has found application

The use of HPLC in analytics

- Pharmacy: Control of drug purity, testing the stability of active substances, monitoring drug concentrations in the blood (TDM).

- Food analysis: Detection of aflatoxins, determination of vitamin, preservative or caffeine content in beverages.

- Medical diagnostics: Determination of hormone levels, tumour markers and newborn screening.

- Forensic Science and Toxicology: Detection of drugs, doping substances and poisons in biological material.

As you can see, there are many analytical applications, but that’s not all. HPLC, like any chromatography, is a separation technique. It allows different substances to be separated. This ability can also be used to purify substances.

The use of HPLC in preparative chromatography

- Preparative HPLC: By using larger diameter columns and a fraction collector, it is possible to separate chemical substances for purification. The preparative scale allows for the purification of substances in quantities ranging from milligrams to grams. It is used in research and development laboratories, particularly in the chemical and biotechnology industries.

- Industrial HPLC: In this case, the chromatography columns are even larger and the pumps are adapted to higher flow rates. Industrial systems are used for effective large-scale purification, e.g. in biotechnology plants. They enable the purification of tens or even hundreds of grams of substances (e.g. proteins).

Summary

I hope this article has given you a basic understanding of how HPLC works. You can find out more about separation theory, column types and separation types in the next articles in this series.

Literature:

- Kocjan R. (red.), Chemia analityczna. Analiza instrumentalna, Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL.

- Namieśnik J., Jamrógiewicz Z., Pilarczyk M., Torres L., Przygotowanie próbek środowiskowych do analizy, Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne.

- Walenty Szczepaniak, Metody Instrumentalne w analizie chemicznej, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN

Grafika

Cyberwork 95, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons