Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is one of the most commonly used techniques in molecular biology. It allows for the rapid replication (amplification) of a specific DNA fragment in vitro. Developed in 1983 by Kary Mullis, it has become the cornerstone of modern diagnostics, scientific research and forensics. Given its wide range of applications, it is not surprising that Mullis received the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

How does PCR work?

The basis of the PCR technique is a chemical reaction catalysed by a chain polymerase. It involves the attachment of complementary nucleotides to single-stranded DNA. The key to using this reaction in vitro is the use of an enzyme that is resistant to high temperatures. It is derived from the bacterium Thermus aquaticus, which is found in hot springs. This allows the denaturation of double-stranded DNA, which is necessary to start the reaction. Denaturation takes place at temperatures above 90 degrees.

PCR is based on the cyclical repetition of three main stages, which take place in a programmable device called a thermocycler.

The reaction requires the presence of the following components:

- Matrix DNA: The fragment of DNA to be replicated.

- Primers: Two short, single-stranded DNA sequences (approx. 18–30 nucleotides) complementary to the opposite ends of the amplified fragment. They determine the start of synthesis.

- Nucleotides (dNTPs): Building blocks (A, T, C, G) for the synthesis of a new DNA strand.

- Thermostable DNA polymerase (Taq polymerase): An enzyme that catalyses the synthesis of a new DNA strand and is resistant to high denaturation temperatures.

- Buffer: Provides an optimal environment (pH, salt concentration) for the enzyme.

- Magnesium ions Mg2+: A cofactor essential for the proper functioning of polymerase.

Steps of the PCR reaction

- Denaturation (approx. 92 °C – 98 °C): At this temperature, the hydrogen bonds stabilising the DNA double helix break. The double-stranded DNA unravels into two strands.

- Annealing (50 °C – 65 °C): The temperature is lowered, allowing the primers to attach (anneal) to complementary sequences on the single-stranded template.

- Elongation (approx. 72 °C): The DNA polymerase adds new nucleotides, starting from the 3′ end of the primer, synthesising a new, complementary DNA strand.

Each cycle doubles the amount of amplified DNA, leading to an exponential increase in the number of copies. The process is usually repeated 20–40 times.

How to design starters?

Proper primer design is crucial for the specificity and efficiency of PCR reactions. The main principles are:

- Length: Primers should consist of 18–30 nucleotides.

- Melting point (Tm): It should be similar for both starters (e.g. in the range of 55 °C to 65 °C). The difference should not exceed 5 °C.

- GC content: The optimal GC content in starters is 40–60%. Too high a GC content may lead to stronger hybridisation.

- Avoiding secondary structures: Primers should not form structures between themselves (e.g., primer-primer dimers) or within their own molecule (e.g., hairpins), especially at the 3′ end. Dimerisation of primers at the 3′ end is particularly critical because polymerase can initiate synthesis from such a site, producing unwanted products.

- Specificity: Primers must be complementary only to the target sequence of the template DNA.

How do get the result?

The method of analysing the results depends on the type of PCR reaction performed:

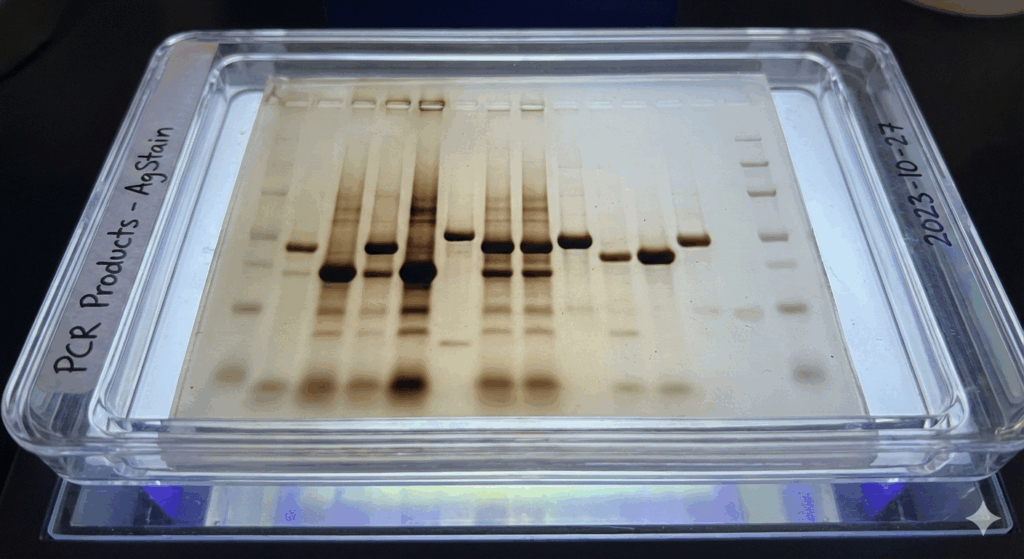

- Conventional PCR (End-point): In a classic PCR reaction, the reaction outcome must be analysed to obtain the result. Most often, the reaction products are visualised and separated by agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments migrate in the gel under the influence of an electric field, and their molecular weight is determined in relation to a standard (mass ladder). The bands (amplification products) become visible after staining the DNA (e.g. with ethidium bromide) and exposing it to UV light.

- qPCR (Real-Time PCR): The analysis is based on Ct values and melting curves (Tm) for non-specific DNA-binding dyes, which allows for the assessment of product purity and specificity. See below in the modifications section.

- dPCR (digital PCR): The result is statistically analysed based on the number of positive micro-reactions, providing the absolute number of DNA copies in the sample.

PCR modifications

The PCR technique has evolved, giving rise to numerous modifications that increase its applicability and precision.

RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription PCR)

It involves transcribing RNA into cDNA (complementary DNA) using the enzyme reverse transcriptase, followed by a standard PCR reaction.

This enables gene expression analysis (measuring mRNA levels) and detection of RNA virus genomes (e.g. SARS-CoV-2). It is a key technique in virological diagnostics.

qPCR (Real-Time PCR)

qPCR is also known as Real-Time PCR or real-time PCR. Unlike traditional PCR, it allows for quantitative analysis of the amplified product during the reaction, rather than only after it has been completed. For this purpose, it uses fluorescent dyes (e.g. SYBR Green) or special probes (e.g. TaqMan), whose fluorescence is monitored in each cycle. The more amplified material there is, the stronger the fluorescence level.

The quantitative result is based on the cut-off cycle (Ct), i.e. the cycle in which fluorescence exceeds the background level. The lower the Ct value, the more of the initial matrix was present in the sample.

dPCR (digital PCR)

dPCR is the most sensitive method for quantitative DNA determination. It involves separating the reaction mixture into thousands (or millions) of microscopic, separate reactions (droplets or wells). Amplification occurs in each micro-reaction, and at the end, those in which amplification occurred (positive result, ‘1’) and those in which it did not (negative result, ‘0’) are counted. This allows the absolute number of DNA template molecules to be counted directly without the need for a standard curve, making it extremely accurate.

Other Modifications

Multiplex PCR: Enables the amplification of multiple different DNA fragments in a single tube using multiple primer pairs.

Nested PCR: Uses two pairs of primers and two successive rounds of amplification, which increases the specificity and sensitivity of the reaction, reducing non-specific products.

Application of PCR

PCR technology has revolutionised many fields of science and practice.

Scientific Research

- Cloning and genetic engineering: Propagation of specific genes for further manipulation, modification, and cloning into expression vectors.

- Gene expression analysis: Use of RT-qPCR for quantitative measurement of gene transcription levels (mRNA).

- Phylogenetic and evolutionary studies: DNA analysis to determine the relationship between species.

- Mutagenesis: Introducing specific changes in the DNA sequence.

Forensic science

- Individual identification: Analysis of short tandem repeats (STR) from minimal samples of biological material (e.g. saliva, blood, hair) to create a genetic profile (DNA fingerprinting) for the identification of perpetrators or victims of crimes.

- Establishing paternity: Comparison of genetic profiles.

Pharmacy and Medicine

- Diagnosis of infectious diseases: Rapid and sensitive detection of genetic material of pathogens (viruses, bacteria, fungi, e.g. HIV, SARS-CoV-2, Lyme disease) in clinical samples.

- Oncological diagnostics: Detection of mutations and genetic changes associated with cancer.

- Pharmacogenomics: Identification of gene variants that influence a patient’s response to drugs.

- Transplant monitoring: Detection and measurement of donor genetic material for early detection of transplant rejection.

Other Applications

- Agriculture and veterinary medicine: Identification of plant varieties, pathogens and animals.

- Archaeology: Analysis of ancient DNA (aDNA).

- Food quality control: Detection of microbiological contamination or adulteration (e.g. identification of meat species). Detection of microbiological contamination or adulteration (e.g. identification of meat species).

Literature

- Mullis K. B. (1990). The unusual origin of the polymerase chain reaction. Scientific American, 262(4), 56-65.

- Innis M. A. et al. (1990). PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press.

- Kubista M. et al. (2006). The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 27(2-3), 95-125.

- https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/technical-documents/protocol/genomics/pcr/standard-pcr

- https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/technical-documents/protocol/genomics/pcr/pcr-qpcr-dpcr-assay-design

- Taylor S. D. et al. (2019). Digital PCR: a critical review of theory and application. Biomolecular Detection and Quantitation, 18, 100080.

- https://zpe.gov.pl/pdf/P1HrrXrst

- https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1TAQ